2020 Presidential Election Analysis

Kayla Manning, Harvard College

Incumbency and Elections

October 3, 2020

The Incumbent Advantage

Since 1948, 72.7% of sitting presidents have won re-election, with only 3 incumbent candidates failing to earn a second term. However, incumbency status alone does not motivate voters to re-elect a sitting president.1 Instead, incumbent candidates reap the benefits of structural advantages such as increased media coverage, an early start to campaigning, and the power to influence state- and local-level funding. For this blog post, I use individual incumbency status as a proxy for the many variables that may benefit an incumbent candidate.

With the 2020 election just a month away, this blog post considers how the incumbent advantage may factor into the 2020 outcome.

Visualizing Federal Grant Aid and COVID-19 Relief Aid

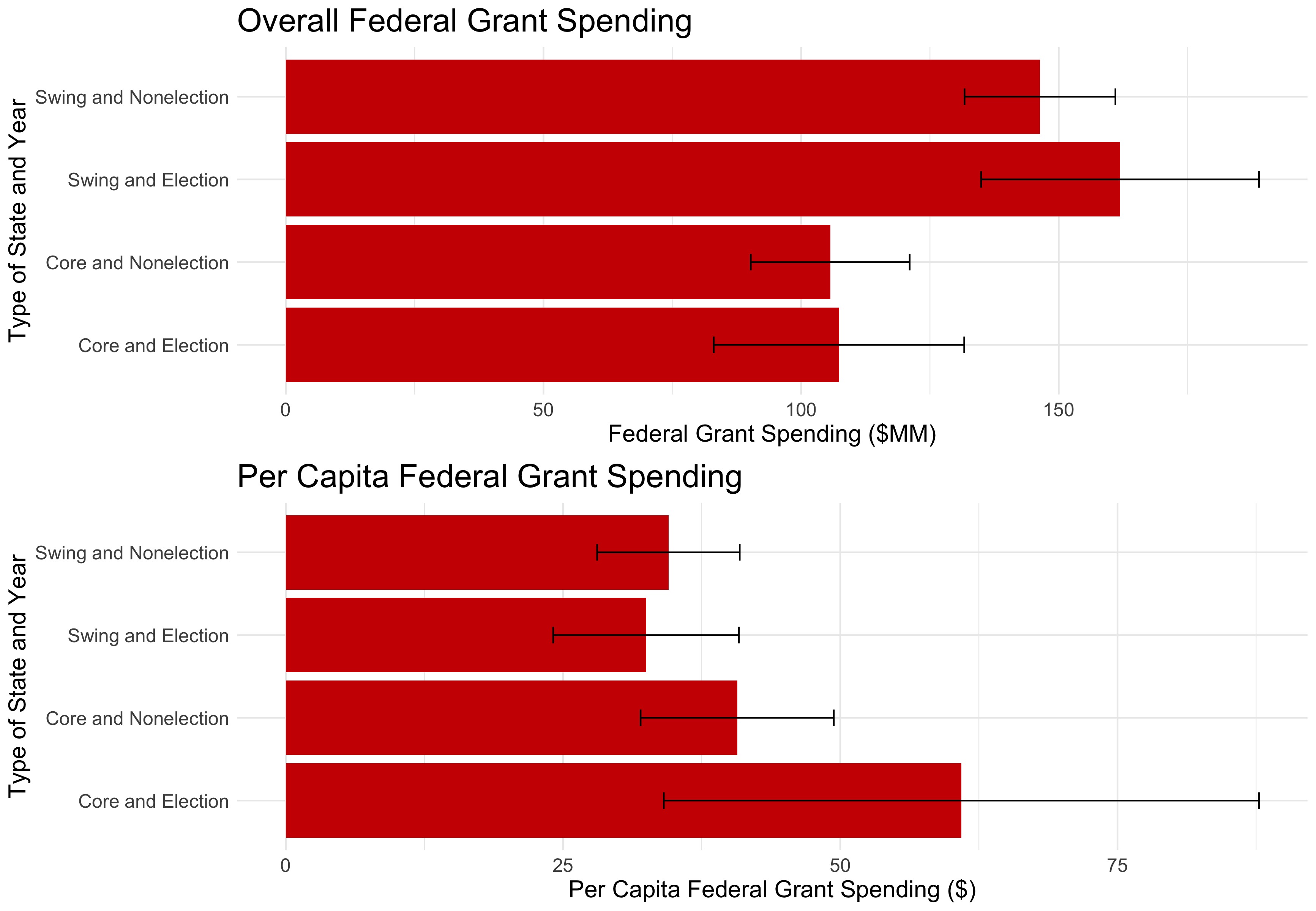

Incumbents run their re-election campaigns on their track records, and voters may feel more inclined to support candidates that direct federal dollars to their localities. A vast body of political literature explores the influence of federal spending on elections.2 Due to the possibility of federal spending on voter behavior, incumbent candidates reasonably desire to direct more funds toward battleground states in comparison to core states unlikely to swing in one direction or another. Overall, it appears that the incumbent party does focus a greater volume of federal dollars on swing states3 relative to states core to their base, with a greater emphasis on election years.

However, the states classified as “swing” states have much larger populations relative to the “core” states.4 What happens when we control for this? It turns out that per capita federal grant spending is greatest in core states during election years:

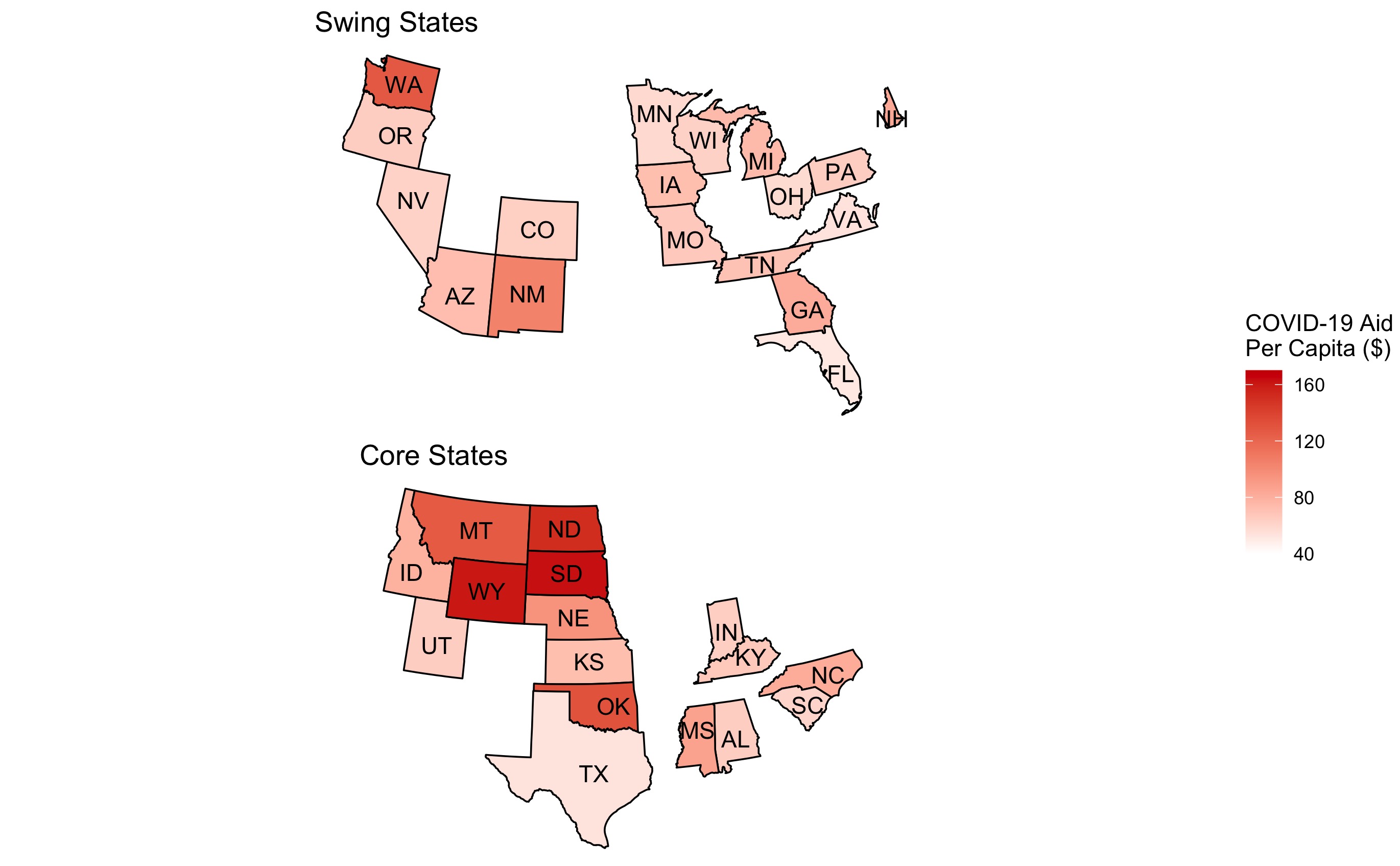

One would think that incumbents would strategically pour more dollars into battleground states in an attempt to sway the electoral college, and that appears to be the case when looking at the absolute totals of grant dollars. However, controlling for population size eliminates this trend. How does this pattern hold for COVID-19 relief funding? The below maps of per capita COVID-19 grant money for core and swing states confirm that the same pattern holds, with the sparsely populated core states receiving the greatest amount of federal dollars per capita:

Since federal spending patterns have followed similar patterns in the age of COVID-19 as overall federal spending in other election years, the spending patterns of Trump’s administration should not disqualify him from receiving incumbent advantages stemming from federal funding.5 With that in mind, I will build upon previous models using incumbency as a predictor to forecast the 2020 outcomes.

Comparing Last Week’s Regression to PollyVote’s Time for Change Model

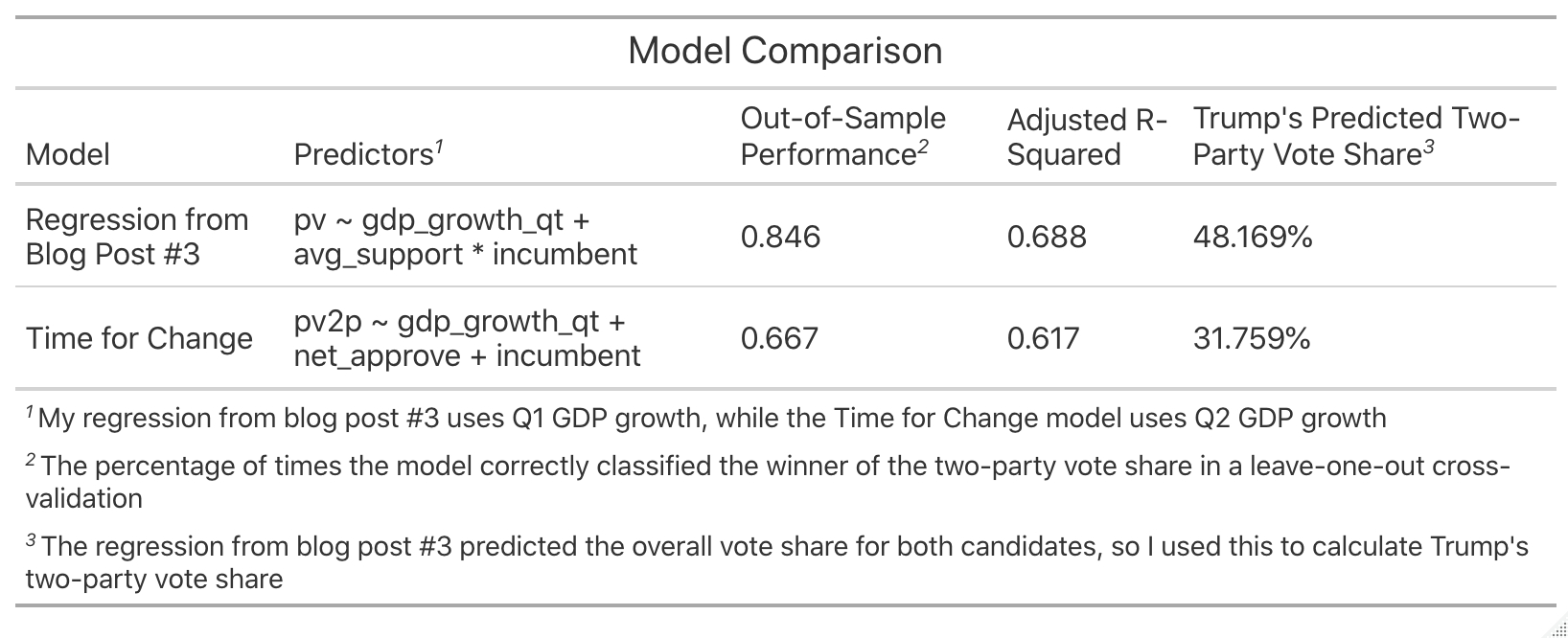

As one of the few major polls that predicted a Trump victory in 2016, PollyVote’s Time for Change model earned the respect of forecasters around the country. The model predicts the two-party popular vote of the incumbent party from Q2 GDP growth, Gallup approval polls, and incumbency status. The model has an adjusted r-squared of 61.7% and correctly classified the popular vote winner in 66.7% of post-WWII elections in a leave-one-out cross-validation. For 2020, it predicts that Trump will win 31.8% of the two-party popular vote.

Last week’s regression mapped popular vote share from Q1 GDP growth, polling numbers from 6 weeks before the election, incumbent status, and the interaction between incumbency and poll numbers. It had an adjusted r-squared of 0.688 and correctly classified 76.9% of the past elections in leave-one-out cross-validation. The model predicted that Joe Biden would receive approximately 51.2% of the overall popular vote and Trump would earn 47.6% of the popular vote, which amounts to a two-party vote share of 48.2% for Donald Trump.

When looking at the above numbers, it appears that my regression model performs better in a leave-one-out cross-validation, explains more variation in the historical data, and predicts a closer election in 2020. Even though these metrics appear to favor my regression over the Time for Change model, one cannot confidently classify one model as better than the other. Given the unusual nature of 2020, a model that performs extremely well on historical data may not serve as the best predictor for this year’s election. However, the relatively strong performance in the leave-one-out cross-validation takes away some concern about overfitting. Both of these models incorporate incumbency, but will Trump’s incumbency status help him out like the models predict, or could it potentially hurt him?

Trump and Incumbency

After numerous controversies, Donald Trump’s 2016 victory taught us that he could quite possibly shoot someone in the middle of Fifth Avenue and not lose any voters. However, 2020 is a new race.

The horrific Q2 economic numbers, his downplaying of the threat of COVID-19, and his years of tax avoidance should hurt his re-election chances. In the face of this adversity, however, Trump’s approval ratings have remained relatively stable. Incumbents typically benefit from greater media coverage, and Trump’s antics over the past four years have earned him his fair share of air time. In our deeply polarized political environment, this additional attention likely energizes his base. After all, his 2016 victory proved that many of his supporters do not mind the controversy surrounding him. On top of his pre-existing base, Trump still has managed to convert some people in 2020 that did not support him in 2016.

On the other hand, incumbents may also face backlash for factors outside of their control.6 The COVID-19 pandemic, rampant wildfires, racial injustice protests, destructive hurricanes, and more have made 2020 a year of chaos, destruction, and confusion. In the midst of it all, however, Trump’s base has shown that it will support him even while he openly brags about sexual assault, mocks disabilities, and neglects to denounce white supremacists. After Donald Trump’s controversial victory in 2016, I believe that his loyal base will not attribute the disasters of 2020 to their beloved leader, whether he is actually to blame or not. In my opinion, most people that fault Trump for any of the past year’s disasters were unlikely to support him in the first place. While Trump’s incumbency status may not have the power to carry him to victory, I do believe that the sitting president’s incumbency advantage will help him win over some voters.

In the coming weeks, my blog posts will focus on campaign activity and unexpected events, which came at the perfect time, given the last week’s presidential debate, Donald Trump’s recent COVID-19 diagnosis, and the battle over RBG’s Supreme Court vacancy.

-

[Brown, 2014] Brown, A. R. (2014).Voters Don’t Care Much About Incumbency.Journalof Experimental Political Science, 1(2):132–143. ↩

-

[Kriner and Reeves, 2012] Kriner, D. L. and Reeves, A. (2012).The influence of federal spending on presidential elections.American Political Science Review, pages 348–366. ↩

-

This use of the terms swing and core comes from the data on federal grant allocations from 1984-2016 obtained from Kriner and Reeves, 2012. The federal spending data comes from their 2012 work, cited in the above footnote. ↩

-

This graphic compares the populations in swing versus core states. ↩

-

This look at federal spending only scratches the surface in terms of the impact of COVID-19 on the election. While I posit that Trump’s spending patterns will likely have minimal unique effects on the 2020 outcome, there are some interesting implications of how COVID-19 deaths and numbers could impact the races of individual states. In his discussion of FiveThirtyEight’s forecast model, Nate Silver mentions the possiblity of covariance between states such as New York and Arizona that have faced similar difficulties with COVID-19 but are otherwise very different. This level of thinking is beyond the scope of these maps of COVID-19 relief aid, but it is interesting to consider in an abstract sense. ↩

-

[Achen and Bartels, 2017] Achen, C. H. and Bartels, L. M. (2017). Democracy for realists: Why elections do not produce responsive government, volume 4. Princeton University ↩